1 Comment

Myth No. 4 - Debunking What We've been told about medical malpractice - five myths about lawsuits8/21/2020

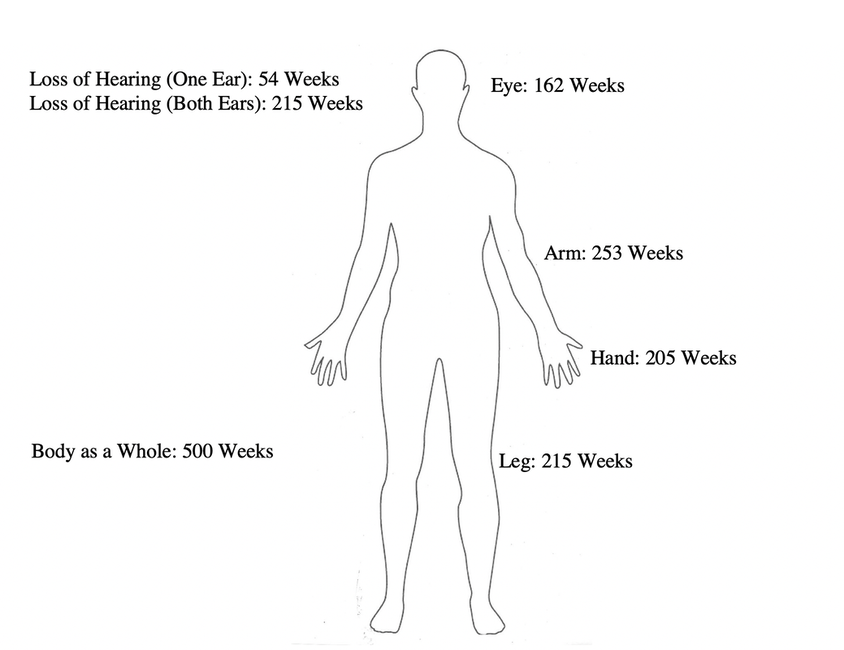

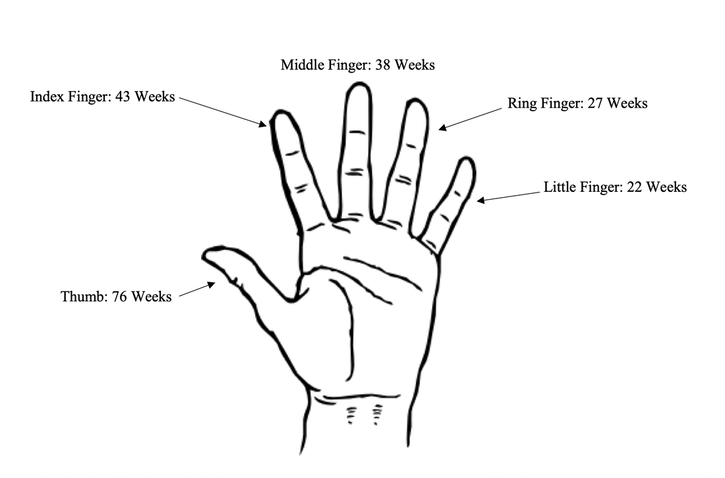

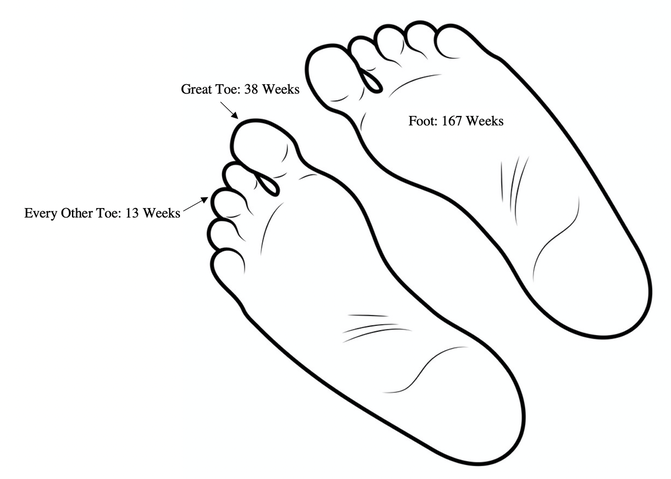

How do they get to that number? Working through Illinois Workers' Compensation settlements7/27/2020 By: Angie Zinzilieta, Partner You may have heard that workers’ compensation settlements work differently than a personal injury lawsuit settlement. In Illinois, workers’ compensation settlements work require some math. The following post is based on Illinois workers’ compensation law. Each state has its own laws and rules concerning workers’ compensation cases. QUICK VOCABULARY: WC workers’ compensation AWW average weekly wage (This is the average amount you were making for the 52 weeks prior to your workplace injury.) TTD total temporary disability (This is similar to an unemployment payment. In Illinois, this amount is 2/3 of your AWW.) PPD permanent partial disability (This is typically what is considered your WC settlement. Employers are required to pay PPD benefits to injured workers suffering from an amputation, physical impairment, or disfigurement caused by job-related injuries, but is able to perform work at some level.) PTD permanent total disability (A complete disability that leaves an employee permanently unable to do any kind of work for which there is a reasonably steady job market. PTD benefits entitle an employee to a weekly benefit of two-thirds of their average weekly wage, subject to certain minimum and maximum limits, for life.) In Illinois, your PPD is calculated as follows: (60% of AWW) X (Value of Body Part)(% of Disability) = PPD The percentage of disability is based on any residual effects of your workplace injury. For example, you may have limited range of motion or permanent restrictions, or you may be unable to do activities that you were able to do before your injury. The “Body Part Value Charts” are below: EXAMPLE OF HOW A WC SETTLEMENT WOULD BREAK DOWN:

Sandy injured her back carrying a large package from her delivery van to a customer's door. Sandy went to the doctor and was diagnosed with a disc injury. Ultimately, after physical therapy and epidural injections, Sandy was required to have a disc replacement surgery. Sandy can no longer bend repetitively or lift more than 30 pounds, and her spinal surgeon has placed her on permanent restrictions prohibiting such. In all, we believe that Sandra has suffered a PPD of 40% Body as a Whole. In the year prior to her injury, Sandy made $1,000 per week before any taxes, insurance, 401(k), etc., were taken out. What is Sandra's AWW? Sandra's AWW is $1,000. What is Sandra's PPD rate? 500 weeks X 40% = 200 weeks How much would Sandra's PPD award be? 200 weeks X ($1,000 X 60%) = $120,000 In Illinois, attorney's fees are capped at 20%. So, if Sandra received a PPD award for $120,000, then the attorney's fees would be $24,000.

Q. Will I lose my job because I filed a workers’ compensation claim?

A. No. Both Illinois and Missouri have laws which prevent your employer from retaliating against your for filing a workers’ compensation claim. If your employer fires you or retaliates against for filing a workers’ compensation claim, you have a cause of action against your employer. Q. If I file a workers’ compensation claim, will I be able to see my own doctor? A. In Illinois, you have the RIGHT to see two doctors of your choice. However, in Missouri, you must see the doctor that the workers’ compensation insurance company chooses for you. On several occasions, injured workers have hired our team midway through their treatment. Even in Illinois, the workers’ compensation claims adjustor falsely tells our clients that they have to go to a doctor of the insurance company’s choosing. This is not correct. Typically, it isn’t until our team gets involved that the client finally gets the treatment they needed from highly qualified doctors of their choosing. Q. Does my employer have to pay for my workers’ compensation benefits directly out of their pocket? A. No. Employers are required to carry workers’ compensation insurance. This is very similar to how we all have to carry car insurance to drive a car. When you’re involved in a workplace injury, the insurance company pays your benefits. Q. I live in Missouri, but I work in Illinois. Where do I file my workers’ compensation case? A. If your employer is located in Illinois and you were hurt in Illinois, you would file in Illinois. Q. How much will I be paid if I have to be off work for my injury? A. The payment you receive for having to be off work because of your injury is called Temporary Total Disability or “TTD.” You are entitled to 2/3 of your average weekly wage or “AWW.” Your AWW is calculated average the amount you were paid for the year prior to your injury. So, for example, let’s say that you are hurt at work and you make $40,000 per year before taxes and everything else is taken out. Your TTD rate would be $26,666.67 per year or approximately $513 per week. You would receive a check for approximately $513 per week. Q. How is the lawyer paid? A. The lawyer is paid based off of what is a called a “contingency fee.” That means our team doesn’t get paid until you are paid. In Illinois, the fee is capped at 20%. In Missouri, the fee is capped at 25%. Q. My employer offered me a light duty job. Do I have to take it? A. Long answer short, yes. As long as the light duty job is within your doctor-recommended restrictions, you should take the employer up on the offer. Not accepting the position could act as a voluntary quitting on your part, which could result in your benefits being cut off. For Immediate Release

The National Trial Lawyers is pleased to announce that Angie Zinzilieta of Wendler Law, PC in Edwardsville has been selected for inclusion into its Top 40 Under 40 Civil Plaintiff Trial Lawyers in Illinois, an honor given to only a select group of lawyers for their superior skills and qualifications in the field. Membership in this exclusive organization is by invitation only and is limited to the top 40 attorneys in each state or region who have demonstrated excellence and have achieved outstanding results in their careers in either civil plaintiff or criminal defense law. The National Trial Lawyers is a professional organization comprised of the premier trial lawyers from across the country who have demonstrated exceptional qualifications in criminal defense or civil plaintiff law. The National Trial Lawyers provides accreditation to these distinguished attorneys, and also provides essential legal news, information, and continuing education to trial lawyers across the United States. With the selection of Angie Zinzilieta by The National Trial Lawyers: Top 40 Under 40, she has shown that she exemplifies superior qualifications, leadership skills, and trial results as a trial lawyer. The selection process for this elite honor is based on a multi-phase process which includes peer nominations combined with third party research. As The National Trial Lawyers: Top 40 Under 40 is an essential source of networking and information for trial attorneys throughout the nation, the final result of the selection process is a credible and comprehensive list of the most outstanding trial lawyers chosen to represent their state or region. To learn more about The National Trial Lawyers, please visit: http://thenationaltriallawyers.org/. |

LOCATION |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed